Despite years of build-up, the new skilled nursing payment model has flown under the radar since its implementation. Operators assess the impact.

By Jeff Shaw

In the years leading up to the implementation of the Patient-Driven Payment Model (PDPM), there was plenty of discussion and handwringing over the impact it would have on the skilled nursing industry.

Officially launched on Oct. 1, 2019, by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the model was supposed to be a sea change for healthcare billing and services. The impetus, at the time, was because the prior payment system overemphasized funding physical therapy, according to CMS.

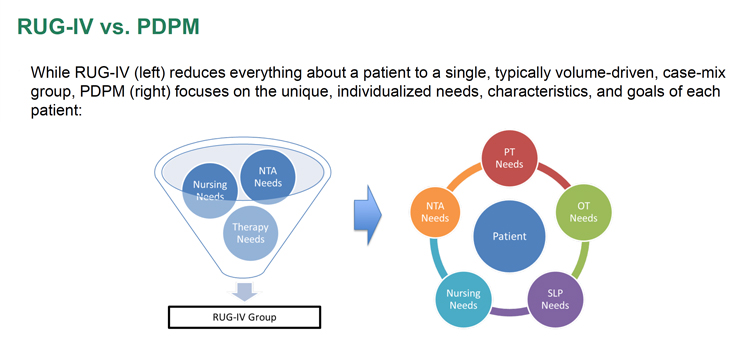

“[The prior model created] an incentive for [skilled nursing] providers to furnish therapy to patients regardless of the patient’s unique characteristics, goals or needs. PDPM eliminates this incentive and improves the overall accuracy and appropriateness of payments by classifying patients into payment groups based on specific, data-driven patient characteristics, while simultaneously reducing administrative burden on providers.”

But in the nearly five years since the program began, little has been said about it outside of skilled nursing billing departments.

There are two main reasons for this relative silence. For starters, just five months after the program was implemented, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Skilled nursing operators, quite simply, were dealing with bigger problems.

According to Fred Bentley, a managing director focused on long-term care and seniors housing at ATI Advisory, a healthcare research and advisory firm, the outbreak turned concerns about PDPM into a “nothingburger.”

“In the early days, skilled nursing facilities were ground zero for the worst of the pandemic,” says Bentley. “We were faced with the biggest existential threat that the industry could face, short of an asteroid strike.

“PDPM was a big deal, it was a sea change. But we had patients dying, we had staff getting sick. At that time we just said, ‘We’ll deal with PDPM when we deal with it.’”

The second reason for the lack of fanfare is, basically, that operators prepared and implemented the program well, according to Janine Finck-Boyle, vice president of health policy and regulatory affairs at seniors housing advocacy organization LeadingAge. While there was considerable angst leading up to the implementation, it was simply time to tear off the Band-Aid.

“The decision was made,” says Finck-Boyle. “Nursing homes had to move forward, or they couldn’t get paid.”

What changed?

Despite the public silence on the topic, stakeholders agree that PDPM marked a major shift for skilled nursing operators.

“Changing an entire methodology changes the way everyone in the nursing home thinks about care, documentation and coding, which takes training and time to adjust to,” says Josh Simpson, partner in the healthcare finance practice of Meridian Capital Group.

“Since PDPM is much more detailed, it takes all disciplines to be involved in the process to make sure everyone is coding properly,” adds Simpson. “One person missing one item can have a significant impact on the payment outcome.”

Finck-Boyle agrees, noting that a facility’s entire interdisciplinary team is involved in payments now, not just care. This is important because payments are based on the full scope of care a patient needs, rather than the straightforward fee-for-service model that had been in place for decades.

“Most residents in a short-term unit have comorbidities. They might be there for one main service — rehab, wound care — but they could be diabetic, HIV-positive, or have respiratory issues like COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]. Those are also being cared for,” says Finck-Boyle. “With PDPM, those assessments are done with full team members. You’re getting the full picture. Everybody’s documenting for the payment system.”

This renewed focus on the whole patient also meant taking behavioral health issues into account.

“For patients with behavioral health challenges, there was an increased payment associated with that,” says Bentley. “Figuring out how to serve that population, how to staff to that, there was an adaptation that had to happen there.”

Operators also had to work closely with their electronic health record (EHR) providers ahead of PDPM’s implementation to make sure the programs were being used properly for the new billing method.

“I can’t speak for every nursing home in the country, but for the majority of members, the pain points came to the integration with EHR and the training, making sure all those processes were in place,” says Finck-Boyle. “But once nursing homes got their plans together, with the EHR vendor helping, they figured out how to work with their interdisciplinary team and move forward.”

“I wouldn’t say it was smooth,” she adds. “There were definitely bumps and learning curves.”

The implementation of PDPM might have even pushed some skilled nursing operators to implement or improve records, which is a long-term positive for the industry.

“I’ll be honest, long-term care and nursing homes specifically are at the bottom when it comes to technology resources,” says Finck-Boyle. “It could’ve gone faster. That’s one of the areas we advocate for: technology in long-term care.”

It also helped that the industry associations — the American Seniors Housing Association, Argentum, LeadingAge and the American Health Care Association — helped providers prepare for the implementation, Bentley notes.

“I’ll give the industry groups credit for doing everything they could for their members to understand the payment models and how it worked. It did require some changes. One is they had to get a lot better at documentation, which is not sexy stuff. But if your payment is contingent on accurately coding the underlying needs of your residents, you’d better get good at it.”

Is PDPM a success story?

Just because operators adapted to PDPM doesn’t mean they approve of it. So how do stakeholders view the success of PDPM as a healthcare payment system?

Most seem to think PDPM has met its goals.

“It more accurately reflects the entirety of the patient’s healthcare needs and is more patient-centered,” says Simpson. “[The prior system was] only taking one element of the equation into account — therapy. PDPM is significantly more inclusive, which ends up with overall better care.”

“It’s a more accurately balanced system for payment,” adds Finck-Boyle. “You’re actually looking at the clinical characteristics of a resident.”

Bentley isn’t willing to call it a success outright but says it’s a step in the right direction.

“The goal of PDPM was to better connect or link reimbursement to the underlying acuity and clinical needs of the residents, and to get away from a system that incentivized skilled nursing facilities to maximize therapy minutes,” says Bentley.

“To what extent is the payment model really linked to underlying need and reflective of that? Certainly, it’s an improvement over the old system where there wasn’t a linkage there, but it’s hard to prove one way or the other.”

Finck-Boyle notes that part of the success was the long lead time before implementation and the willingness of CMS to help prepare operators.

“It did take some time; there was a lot of training,” she says. “But there was a big ramp-up.”

Another factor for the silence, Bentley suggests, is that CMS actually pays more to operators now than it did under the previous payment system.

“The CMS analysis — and there’s a debate about its accuracy — found that PDPM resulted in net increases in payments to skilled nursing as an industry. It’s not surprising that if we as an industry benefitted, it behooves us not to make a big deal out of it. If it resulted in a net decrease, we’d hear a lot about this. I think, candidly, that has to play into this a bit.”

At the very least, notes Bentley, the change to PDPM could’ve gone a lot worse.

“I remember the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. There were some major changes. That was viewed as Armageddon for the industry,” says Bentley. “Compared to that, PDPM has been a lot less tumultuous.”