By Eric Taub

When Bluetooth burst on the scene, Procter & Gamble thought it would be a great idea to incorporate the technology into its Oral-B toothbrushes.

We can see how well that went over.

And now that we can buy what is claimed to be the world’s first artificial intelligence (AI)-powered office chair from Backrobo, you’d be forgiven for thinking that our obsession with this latest technology is another prime example of irrational exuberance.

AI has entered the “inflated expectations phase” of the so-called hype cycle, the point at which a new technology is touted as being able to solve everything. Unfortunately, that’s typically followed by a backlash of disillusionment, as AI companies fail and solutions don’t work.

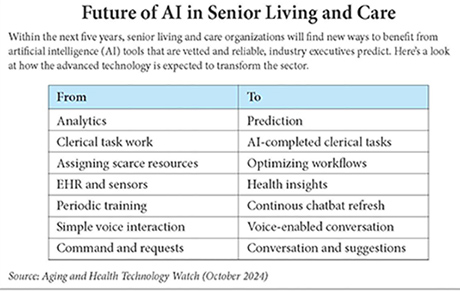

The rapid growth of AI makes this an ideal time to take a rational look at how the technology is applied to senior living. Industry observers and executives believe that, if done right, AI holds great potential to improve senior living operating efficiencies as well as the well-being of its residents.

Several factors are generating heightened interest in the role of AI in senior living. Aging and Health Technology Watch, a market research and analysis platform focused on the intersection of technology and aging, highlighted these forces in its October 2024 report titled “The Future of AI in Senior Living and Care.” They include:

- the rising cost of senior living; the median cost is now $66,000 per year.

- the growth in the number of older adults coupled with fewer available caregivers.

- a challenge in hiring nurses, with 94 percent of nursing homes noting that it’s become difficult to find new workers.

- a growing expectation among residents that technology innovations will be part of the solution.

- the generation of reams of patient data, but not enough actionable insights or proactive recommendations available.

‘AI is a Tool, not a Friend’

“Like every major technology wave — from the steam engine to the smartphone — AI isn’t inherently good or bad,” says Scott Code, vice president of the Center for Aging Services Technologies at Washington, D.C.-based LeadingAge, a coalition of non-profit aging services providers.

“Its impact depends on how providers use it to amplify human connection, not replace it. The real opportunity lies in deploying AI to support staff and enhance resident experiences,” emphasizes Code.

AI works when it is being used as an adjunct for, rather than a replacement of, human interaction. Senior living communities are harnessing AI to rationalize their operations, increase staff efficiencies and resident happiness.

The technology can help salespeople separate true resident prospects from the lookie-loos, free up employees from having to deal with various mundane tasks, and triage resident requests to allow staff to answer those that really need a human touch.

AI can either be utilized to create increased efficiencies, thereby enabling staff to spend more time one-on-one with residents, or it can simply be employed as a way to cut costs by culling head count, without increasing the quality of resident care.

“The unfettered use of AI is bad,” says Derek Dunham, president of Varsity, a Harrisburg, Pennsylvania-based senior living consultancy company. “AI is a tool, not a friend.”

Dunham believes that it’s more important to use AI today as a solution to rationalize back-office work rather than adopt solutions that would encourage residents to interact with an AI portal instead of a human.

Real-Life Examples

Varsity is using AI with clients to harness the reams of data it’s currently collecting and then analyzing the information to find traits among users that will help it close a sale. Its AI solution scores a prospect’s interest in a residence tour or a marketing event and pairs it with the prospect’s ZIP Code and other factors, such as how long it took the individual to make a purchase decision.

Armed with this information, salespeople can more accurately figure out which future consumers are likely to sign on the dotted line.

“With AI, we can see what a prospect looks like that closes in 60 days versus one that takes six months to close. That way we can help salespeople focus on the ones most likely to sign up,” says Dunham.

Varsity has also used AI to help a client reduce resident falls at its community. The facility operator used AI to evaluate several variables, such as a resident’s gait change, where and when the individual walked, and where falls occurred. It then harnessed AI to determine where lighting needed to be improved and what roadway obstacles should be removed.

The result: a 17 percent year-over-year reduction in falls following implementation of predictive risk scoring driven by machine-learning methodologies that were based on that population’s health and environmental data.

Varsity is also using the ChatGPT AI engine to generate customized emails sent to prospective clients based on the needs and style of the residence.

In addition, AI also analyzes questions asked by prospective residents on the client facility’s website to determine what information is missing from the site that would help the company convince an individual to join the community.

The result is that “we’re finding that AI augments the staff, allowing a residence to redeploy the work that people do,” says Dunham.

Dollars and Sense

The danger for senior living owners, Dunham believes, is if executives use the operating efficiencies to cut staff rather than allow them to interact more with residents.

“Industry leaders who see AI as a way to reduce head count are in danger,” he says.

Daniel Levine, executive director of the Avant-Guide Institute, a global trends consultancy, believes that’s a real likelihood.

“Senior living is an industry that’s very profit-based. Good staffing is very hard to find. AI and robots are a godsend to overturn current business models. Robots and AI are becoming cheaper and cheaper, while humans are becoming more expensive,” says Levine, who is based in New York City.

“Corporations will always give lip service to their ability to enhance their caregiving,” adds Levine, “but economics will trump that.”

If the senior living industry doesn’t fall victim to the siren call of increased profits, Levine believes that AI could be of great benefit to the industry.

Some of the positive impacts Levine believes AI can have include harnessing AI to act as a virtual receptionist, using AI to automatically document and summarize health conditions, generate resident progress notes, and create training modules for new residents are some of the positive impacts he believes AI can have.

If implemented smartly, AI-powered augmented reality headsets will enable staff to receive immediate answers as to how to handle patient crises, such as agitation or falls.

Caregivers can be deployed more efficiently, as AI can predict where and when staff are needed and dynamically adjust head count based on time of day.

And case notes can be uploaded to a resident portal so that all caregivers — from family members to physicians and residence staff — have access to the same information and understand who has interacted with a resident and at what time of day.

“Technology streamlines operations; it doesn’t replace the human touch,” agrees Code. “Communities that pair smart automation with purposeful staffing preserve — and even elevate — the personalized experience residents deserve.”

One example: Butlr, a supplier of motion and fall detection equipment to senior living, uses AI to analyze changes in movements that could indicate physical issues, alerting staff to check in on a resident.

The system uses surface temperature measurements rather than cameras to detect changes in movement, thereby not capturing any visual or personally identifiable information, protecting resident privacy.

The technology can detect how many people are in a room, their changing places and body positions and any anomalies over time.

Rather than constantly checking in on all residents based on time rather than need, caregivers can visit only those who actually need help. “Now nurses can become super nurses,” says Honghao Deng, CEO of Butlr, headquartered in Burlingame, California.

“They don’t have to do mundane tasks like knocking on every resident’s door. Instead, this signal processing technology is like having a virtual nurse in every room.”

Senior living communities must not integrate AI willy-nilly, advises John Lariccia, CEO of Atlanta-based WelcomeHome, a provider of customer relationship management software to 3,500 senior living locations.

“AI is very exciting but one needs to trust but also verify,” he says.

“You need to ask the right questions of AI,” Lariccia says, noting that if you ask the technology to summarize the transcript of a conversation, it will even make up part of the discussion if you tell it that a third, non-existent person took part.

The company has found strong utility in using AI to predict the likelihood that a prospect will move in, based on such data as sentiment analysis of recorded phone calls, whether the prospect simply listens or asks questions, and if the individual is keen to engage in multiple community tours and activities.

But what AI couldn’t do well was compose emails that potential and existing residents would like. “In senior living, tone and voice matter,” notes Lariccia. “ChatGPT still lacks warmth and authenticity.”

By creating efficiencies, senior living management can spend more money on higher quality food and additional resident activities, among other benefits, believes Jeff Baum, a teaching professor and consultant who researches AI and senior living applications at Arizona State University’s W. P. Carey School of Business in Tempe.

Inspiren has developed an AI-based ecosystem of communications tools that allow senior living communities to track changes in patient physical behavior, dynamically allocate staff, and ensure that a facility is billing a resident’s family correctly for services provided.

Working with 87 senior living operators across the U.S., Brooklyn, New York-based Inspiren utilizes motion sensors that can track changes in the time a resident spends in bed, on the toilet, or getting out of bed, and correlates any changes with their height, weight, and normal activity levels to predict the likelihood of a fall.

Any anomaly that the system detects will trigger an alert to care staff, allowing the team to take immediate proactive measures to ensure that a fall does not occur.

To improve staff efficiencies, Inspiren identifies the time all clinical activities take, including physical therapy and bathroom care, and AI helps identify when additional staff are needed or caregivers can safely be reallocated elsewhere.

A sensor worn by a staff person automatically registers how much time an individual is spending with a particular resident. That information is automatically entered into the resident’s electronic health record and compared with the level of care that that resident is being charged.

The result: facilities working with Inspiren are recovering additional income, given that “twenty-five to thirty percent of billed care levels are inaccurate,” claims Michael Wang, founder of Inspiren.

Hardly a Panacea

As new aging populations that are more adept at technology enter senior living, there could be a desire by management to introduce AI-powered chatbots or even emotional companions that could serve as a substitute for true human contact.

This would be a mistake, believes Josh Klein, CEO of Emerest Companies, a Brooklyn, New York-based homecare services firm and supplier of nurses for senior living residences, with operations in five states.

“You can’t rely on a machine that has absolutely no empathy,” says Klein. “When there’s no human interaction, patients know it. Currently this type of tool is not giving us good results.”

The exception: Emerest has found that the elderly do like to use AI-powered tools to ask questions that they might be too embarrassed to ask of a real person, such as inquiring about an unexplained spot on one’s body.

“There are a lot of taboo topics that people would not share on a one-to-one basis. But there’s something to be said about a face-to-face interaction. AI works when the answer is just a thumbs up or down response,” says Klein.

Emerest has developed chat rooms for eight to 10 participants. “They schmooze, forget about their problems, and create real-life friendships. AI can’t do that because it will give you a one-to-one experience at best,” notes Klein.

AI is also being used to automate documentation processes, enabling nurses to spend more time with the resident.

The technology has allowed Emerest nurses to more easily detect early signs of conditions such as sepsis and pneumonia because they’re looking more at the patient and less time at their laptop.

“Suddenly our calls to primary care physicians are going up as we experience more medical escalations thanks to AI,” explains Klein.

The company is now experimenting with offering AI tools such as ChatGPT to its caregivers, allowing them to ask questions such as how to calm a resident or defuse family conflicts.

They’re also uploading pictures of wounds to get AI-based assessments and asking for age-appropriate jokes that they can tell that could help improve a resident’s mood.

With all the benefits that AI brings to senior living communities, the technology must be used with care, not as a substitute for human contact or as a way to cut costs by reducing staff.

Socialization is paramount for the elderly, and you can’t improve social interaction with a chatbot, emphasizes Klein.

“AI does not help build a community. A real social setting lets you pick who to speak to. “And when you do so, people flourish.”

— This article originally appeared in the August-September 2025 issue of Seniors Housing Business magazine.