PHILADELPHIA — The wants and needs of the labor force in seniors housing are different today than they were pre-pandemic, forcing operators to adapt on many levels, said Lynne Katzmann, founder and CEO of Juniper Communities. “The gig economy has created a new set of demands on us that we haven’t had to face before.”

Katzmann has her finger on the pulse. Bloomfield, New Jersey-based Juniper is an owner and operator of 29 senior living communities in four states with a resident capacity of 2,300 and 1,750 employees.

Ultimately, workers want more flexibility, Katzmann insists. She cites DailyPay, an app that enables workers to receive their earned wages before the next payday, as an example how technology can be part of the solution.

“The other thing that’s changed radically is that we’re not just tactical anymore. We have to be strategic. That applies to everyone, particularly the leadership at the community level. We’ve got to find solutions to problems we didn’t know we had before. It requires a different set of skills,” said Katzmann.

Couple that with the emotional and physical fatigue that many frontline senior living workers experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, “and I think it’s created a very different environment. We’re looking for slightly different people at the leadership level.”

The comments from Katzmann came during the CEO power panel session at France Media’s seventh annual InterFace Seniors Housing Northeast conference in Philadelphia on Wednesday, Nov. 29.

Valerie Whitman, president and CEO of monitoring systems company EyeWatch LIVE, served as moderator of the panel session. Joining Whitman and Katzmann on stage were fellow panelists Kelly Andress, founder and president of SageLife; Scott Stewart, founder and managing partner of Capitol Seniors Housing; Michael Stoller, CEO of LCB Senior Living; and Michael Uccellini, president and CEO of The United Group of Companies.

The Talent Wars Continue

Whitman asked the senior living executives what changes they’ve observed in the labor market the last few years and whether the industry’s reliance on staffing agencies has waned.

“We’re still spending a good deal of money on agency staffing, but probably about 10 percent or less of what we were during the height of the pandemic,” said Stoller of LCB, who pointed out that the company has taken many steps to attract new workers.

“We have three in-house recruiters in three different parts of our portfolio. We expanded the workforce in almost every area, particularly care, because that was the one area that we had the most problems with [in terms of hiring and retaining people]. It took the entire focus of the company basically to solve that problem,” explained Stoller.

Based in Norwood, Massachusetts, LCB builds and acquires seniors housing communities. There are currently 35 properties in its portfolio across the Northeast, about half of which LCB built from the ground up and the other half it acquired. LCB has grown to become the second largest assisted living provider in New England and expanded into the mid-Atlantic.

Uccellini of the United Group echoed the sentiments of Stoller and added that the talent wars are quite real. “When you’re trying to find people, sometimes they’re not even getting back to you, or you’re trying to get them to do interviews. It’s pretty unprecedented right now.”

Based in Troy, New York, the United Group has developed, owned and managed about 4,000 units in the active adult and independent living “lite” segments of senior living. United Group is currently developing a 164-unit active adult community near Hartford, Connecticut.

United Group is utilizing the services of headhunters and placement agents to recruit new employees. Fixing the labor shortage problem requires the same dogged persistence as turning around a struggling project during the lease-up period, explained Uccellini.

“You look at it six ways to Sunday, and you try everything and anything to get that traffic up and get those leases and get your volume up. That’s the way it feels like in our HR department in terms of what we’re doing to try and get the staff, the talent that we need to run the communities that we have,” said Uccellini.

Meanwhile, the combination of higher wages and rising property insurance premiums is driving up operating costs, said Uccellini. “In some projects that we have our insurance costs per unit equal the real estate taxes per unit. I’ve never seen that before.”

Katzmann said that agency staffing hasn’t posed a problem for Juniper Communities for quite some time. The company’s focus now is on reducing overtime. “We’ve come down considerably [in the use of overtime] in the last year, which is good. We still have more work to do.”

Stoller said LCB has increased pay rates by about 30 percent over the last two years. While that’s negatively impacted margins, it’s one way to retain workers.

“We also have bonus programs — sort of the catch-somebody-doing-something-good kind of programs — that give people other reasons to stay and perform at a higher level.”

Workers want to be recognized for the difference they are making in the lives of the residents and their families. In short, retaining workers requires a much holistic approach than simply raising their level of pay, said Stoller.

Rents Mostly Rebound

Andress of Springfield, Pennsylvania-based SageLife, which operates six communities in three states — Maryland, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania — said rent growth across the company’s portfolio hasn’t been uniform over the past three years.

Rents at SageLife communities that were fully leased before COVID — and which didn’t experience a decrease in occupancy during the pandemic — have remained “very high.” Andress concludes that’s because the residents are satisfied with a proven product and that the families value the services offered.

“We also opened two communities during COVID. Those properties had depressed rents, as we gave concessions to get people in during COVID. So, we need to see double-digit increases at those two communities,” said Andress. Currently, the rents at those two communities are below the market rate.

SageLife also opened a large community post-COVID. “We’re getting slightly lower rent increases there, but the base rent is higher because it didn’t see a dip,” said Andress.

The “dip” of course refers to the occupancy declines and stalled rent growth endured by many owners and operators during COVID.

At Juniper, revenues from 2021 to 2023 across its portfolio rose 14 percent and census increased 12 percent, according to Katzmann.

While rent increases accounted for the majority of Juniper’s revenue growth over the two-year period, the company noted there was a 58 percent increase in level of care and ancillary service charges.

“I just want to make the point that it’s not just your rental rate, it’s not just occupancy. You need to look at ancillary services and level of care as well. And that’s something that we in the assisted living and memory care sector haven’t done as well with over the years,” said Katzmann.

“We’re finally understanding that healthcare is a big part of what we do, and we’re adjusting our systems to be able to capture those revenues,” she added.

A “traditional senior living operator” that offers independent living, assisted living, memory care and skilled nursing, Juniper is not in the active adult space, explained Katzmann.

Stoller of LCB said the company has boosted rents by approximately 30 percent over the past three years.

“It feels to me like at some point [the outsized rent increases] can’t continue, but we aren’t getting pushback. So, it’s pretty amazing. Costs have gone up ridiculously. Margins are finally starting to come back. We need more rent increases long term to get back to what our pro formas were,” said Stoller.

In the active adult space, United Group has been able to achieve rent growth of 10 percent or more in each of the past two years, even among newly constructed properties that are in lease-up mode. “It’s been pretty healthy,” says Uccellini.

Stewart of Capitol Seniors Housing said that many of the dozen operators it works with from coast to coast enjoyed double-digit rent growth in 2022, but that this year the focus was primarily on boosting the occupancy portfolio-wide.

Capitol Seniors Housing ranked as the 45th largest owner of U.S. seniors housing with 32 properties and 4,238 units as of June 1, according to the American Seniors Housing Association.

“I’m glad to hear a tone of occupancy increasing and margins coming back. That’s all positive news and comes at a good time,” said Stewart.

Unlike the hotel and airline industries, which Stewart noted “are crushing it these days,” the business recovery in seniors housing sector has been more gradual.

Still, Stewart said that it’s a mathematical certainty that brighter days are ahead for the seniors housing sector given that the supply pipeline has slowed to a drip and the silver tsunami is on its way with 10,000 Americans turning age 65 daily.

Tough Row to Hoe for Borrowers

Uccellini doesn’t sugarcoat the road ahead for borrowers and lenders. “I think 2024 is going to be very turbulent, very choppy, very difficult in the capital markets. I think 2025 will be very good.”

Most banks today are “pencils down” when it comes to construction financing, and they’re not taking on any new relationships, he said. Furthermore, banks are bulking up their capital reserves in response to turbulence in the capital markets.

Despite the long odds, United Group was able to close a construction loan about a month ago at 280 basis points over the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), which at the time was 5.3 percent. “That was an anomaly. It was very challenging and difficult. It was done with a new lender relationship, which is next to impossible today,” said Uccellini.

The silver lining to the turmoil in the capital markets is that there is going to be plenty of opportunity to buy troubled properties in 2024, Uccellini predicts. There was a significant amount of construction loans originated in 2019, 2021 and 2022 that featured variable-rate financing. The rise in interest rates has put many of those loans under stress. Borrowers seeking to exit those construction loans via bridge financing are likely going to be asked by lenders to put more of their own money into deals in order to secure those bridge loans.

And what is Uccellini’s near-term outlook for interest rates? “I personally don’t think rates are going to start to come down until the very end of 2024.”

Stoller noted that the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank this past spring significantly changed the regulatory environment. In addition to operating in a higher-interest-rate climate, the banks are feeling more pressure internally and externally to balance their portfolios.

“Deals that would not have been considered an issue years ago are now an issue. There aren’t many banks in the industry that are really lending today. So, it’s a double hit on the way you process refinancing and move a project forward.”

Stewart, who described today’s borrowing climate as “brutal,” said Capitol Seniors Housing initially wanted to play the role of contrarian by undertaking new ground-up development when others weren’t. But the banks didn’t cooperate with that game plan, he said, so Capitol Seniors Housing pulled back on the development front.

Stewart described the two schools of thought today amid the current capital markets volatility. Plenty of smart private equity players are biding their time, patiently letting the situation play out. And then there are some developers attempting to forge ahead with new projects in a business climate fraught with uncertainty.

Any glimmer of hope for a recovery in lending activity in 2024 is ultimately tied to the Federal Reserve’s next move on interest rates, said Stewart.

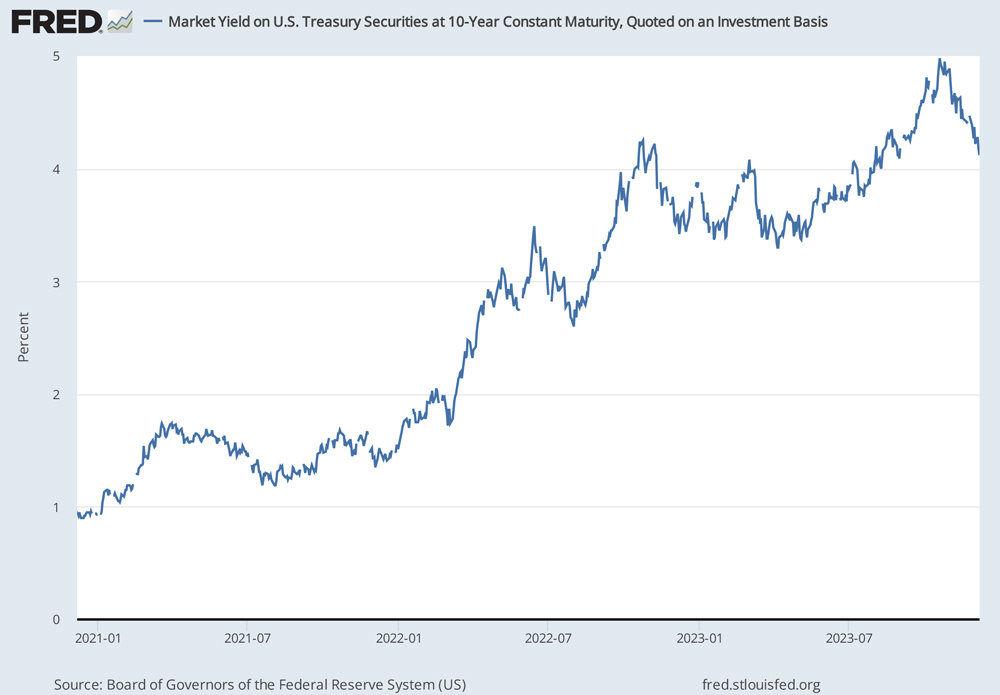

“That’s what kind of put us in this soup. As soon as the Fed started jacking up interest rates, the banks all closed down [the financing spigot],” said Stewart, referring to the Federal Reserve’s 11 rate hikes beginning in March 2022 that took the federal funds rate from near zero to a target range of 5.25 percent to 5.5 percent.

Many banks have hunkered down and are bracing for an onslaught of bad loans in the wake of the run-up in interest rates, according to Stewart. “That has got to sort itself out, and that’s not an overnight thing. It’s going to take a while.”

One reason for optimism: The Wall Street Journal reported on Nov. 27 that interest-rate futures indicated a 52 percent chance the Fed will lower rates by at least 25 basis points by its May 2024 policy meeting.

The Federal Reserve opted today (Dec. 13) to keep the benchmark overnight borrowing rate in a targeted range between 5.25 percent and 5.5 percent. The Fed also penciled in three rate cuts of a quarter percentage point each in 2024 based on the latest economic data showing that inflation continues to moderate.

The Wall Street Journal reports that investors in interest-rate futures markets now believe there is an 80 percent probability the Fed will begin to lower interest rates in March, according to CME Group.

If that comes to fruition, “that’ll be the first domino to go toward the recovery,” said Stewart. “But right now, it’s tough out there. You’ve got some regional banks that are out there playing ball — God love ’em — but the big banks are on the sidelines and just waiting for this hurricane to subside.”

— Matt Valley