PHILADELPHIA — It is common to hear operators proudly profess that it’s their culture that allows them to be top employers in the seniors housing industry, helping to face the massive labor shortage within the sector.

However, “culture” can be a nebulous word, and employee surveys show that what employees say makes for a good culture is far different from what the employers believe, according to Charles Turner, CEO of shift-filling software platform KARE.

Turner, a former president of two operators in previous positions, didn’t pull punches regarding the overuse of the term “culture” in seniors housing, calling it a “lazy word.”

“As an owner and operator, I thought we had a really cool culture. That was true down to the activity director level, but the frontline workers never really bought into what we were doing.”

Turner’s comments came during his keynote address at France Media’s InterFace Seniors Housing Northeast conference, held at the Sheraton Philadelphia Downtown.

Thanks to his software platform’s tens of thousands of seniors housing employees, Turner was able to survey front-line workers to see what was important to them. KARE also gave the same questions to operators, highlighting the difference between what companies thought employees cared about and what those employees actually said.

To begin, Turner gave the profile of a typical front-line caregiver — most are single but with either a dependent child or taking care of a dependent adult. “That’s a lot of personal stresses added to their lives.”

Because of this, Turner says, an employee’s definition of a strong culture is much more individualistic than their company’s.

Top responses for what makes a strong culture to employees included features such as making sure previous shifts have cleaned up before leaving, listening to ideas and needs of employees, having enough staff to prevent burnout and not micromanaging each employee.

Opportunities for advancement are also extremely important, he notes. If there’s no room to grow professionally, a worker becomes a commodity. “If they’re commoditized, that means their goal is to be sold to the highest bidder.”

“These are people that are not making a lot of money,” said Turner. “We try to get them to self-actualization. They’re trying to get rent. It’s a different world.”

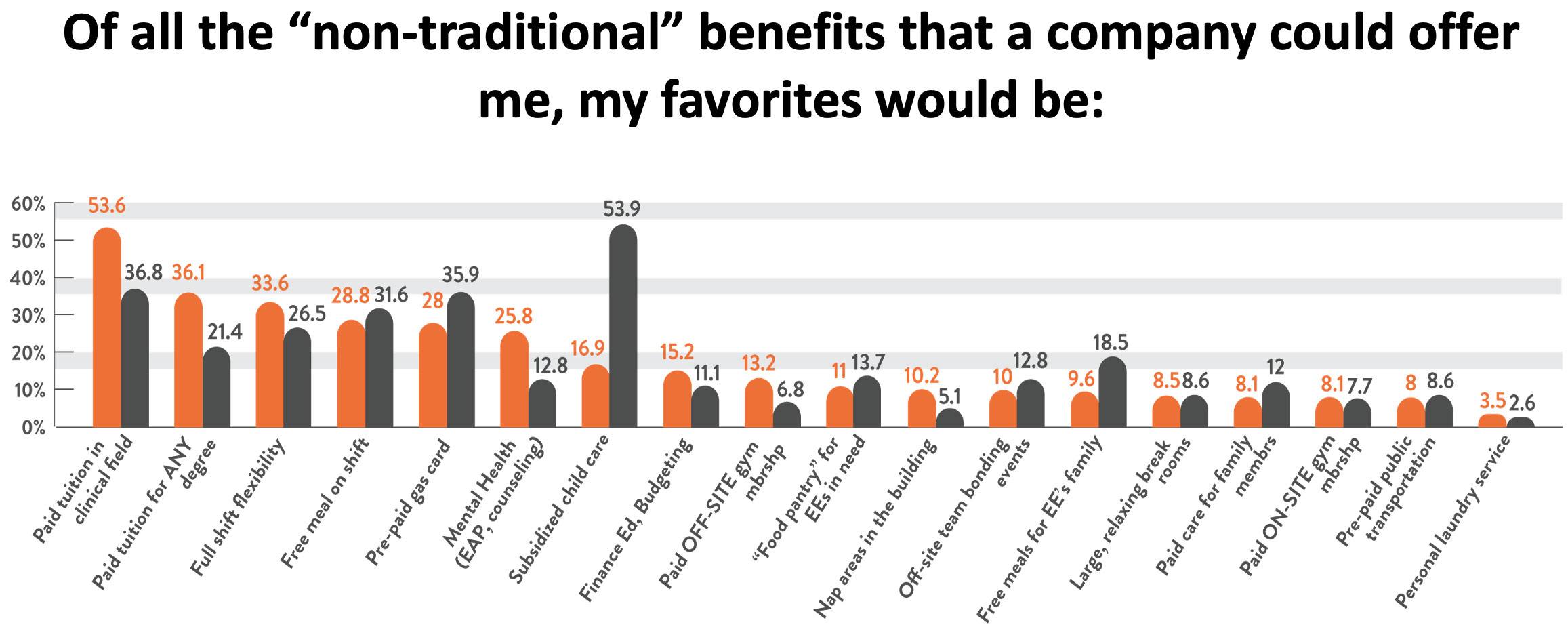

Kare survey results shows what benefits seniors housing workers most want (orange) compared to those that operators believe they want (grey). Click to view larger.

This plays out in the most popular benefits. Many operators tout their benefits, but Turner’s surveys showed that what employers think their workers want does not always line up with reality.

For example, paid tuition is far more popular for workers than employers realized, as well as mental health counseling and shift flexibility.

Meanwhile, many companies think benefits like pre-paid gas cards, free meals and subsidized childcare were more popular among workers than they are.

“[Employees are saying] ‘Don’t give me things,’” said Turner. “’Don’t give me a handout. Help me level up.’”

Turner was quick to note, though, that every community is different, and that operators should simply ask their employees what is important.

“Survey your own employees,” he said. “What do they really want?”

— Jeff Shaw