By Matt Valley

Property valuations have decreased 5 to 10 percent overall across the seniors housing industry due to the operational disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s the expert opinion of Imran Javaid, managing director of BMO Harris Bank, who says the percentage decline can vary depending on the age of the facility, the operator and the

specific asset class.

The respiratory virus, which as of Jan. 24 had claimed the lives of more than 417,000 people in the U.S. and ravaged a large swath of the economy, initially forced the lender into “portfolio management mode.”

“For the first three months of the crisis, all banks kind of hunkered down a bit. It started easing up by the end of summer,” said Javaid, but he was quick to add that the velocity of activity has definitely not returned to the level it was prior to the pandemic.

BMO Harris Bank’s primary focus currently is on serving existing clients, according to Javaid. “We are a pretty active construction lender, but we are only doing new construction for existing clients for the most part right now.”

Javaid’s comments came during a capital markets panel discussion as part of the InterFace Seniors Housing Investment, Development and Operations virtual conference held Dec. 8 and 9.

Moderated by Latoria Thompson, founder and CEO of Latoria Thompson Consulting LLC, the capital markets panel focused on who’s lending, what products are available to borrowers, and how the finance sector has been impacted by the pandemic.

In addition to Javaid of BMO Harris Bank, panelists included Ari Adlerstein, senior managing director, Meridian Capital Group; Lory Brin, head of healthcare real estate, MidCap Financial; Adam Sherman, senior vice president and head of senior care at Live Oak Bank; and Brian Robinson, senior vice president of healthcare finance, First Midwest Bank.

Banks dial back

Debt capital will act as both a driver and a constraint in the seniors housing industry over the next six months, predicts Javaid. While alternative lenders and debt funds will certainly be in the mix to augment the plentiful amount of equity that’s available, institutional banks will face some challenges on the financing front, he believes.

“Our industry is a little bit of a laggard in the sense that when COVID hit, it doesn’t automatically show up in your covenants right away from a bank standpoint. It takes some time to filter through,” said Javaid.

He expects some of the loan covenant compliance issues that began to surface last year will continue to crop up in the first quarter of 2021.“Banks have to deal with that, as do other folks, but banks have a regulated way they have to go about it. So, when you are looking at your portfolio, that will still be a constraint.”

Brin of MidCap Financial says there are a number of seniors housing facilities that were fully stabilized pre-COVID that have “regressed” since last spring and now are in need of a bridge loan solution in order to return to stability.

“There is an understanding that there needs to be some level of liquidity and capital that the sponsor and/or equity partner needs to bring to the table to fund operating shortfalls, or interest shortfalls, to get the property to the place where we’re through the teeth of COVID disruption and back to an environment where properties are stable.”

One silver lining to today’s dislocation in the seniors housing sector is that development is going to be constrained for the next 12 to 18 months, says Javaid. “That’s not such a bad thing, right? It’s good for the industry. There is going to be pent-up demand once the right amount of the population gets vaccinated and people are comfortable.”

Another silver lining to the healthcare and economic crisis is that owners and operators new to the industry have come to realize that seniors housing is an operational business that combines elements of hospitality and healthcare, said Javaid.

“There were a fair amount of folks entering our industry, like the multifamily types, who didn’t view this as really a healthcare business, but they were more focused on the hospitality aspect. So, they were pitching this paradigm shift as all about hospitality, according to Javaid.

“Well, the pandemic probably shifted their thinking for the better in the sense that ‘No, there is absolutely a healthcare component in all of this, including independent living.’”

Financial impact not uniform

Robinson of First Midwest Bank, which lends on skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), assisted living and continuing care retirement communities with a total asset value of $1.1 billion, says the SNFs that were minimally impacted by COVID-19 have financially held up quite well.

“There was a lot of cash that came in via stimulus. If they are able to utilize their purchasing power and have [the necessary] personal protective equipment, we haven’t seen as much of an impact as those that were hit hard by COVID, which makes sense. When we break down the numbers at some of our nursing homes that had larger outbreaks, if we strip out stimulus, we’re seeing [debt-service] coverage ratios that are not where they should be.”

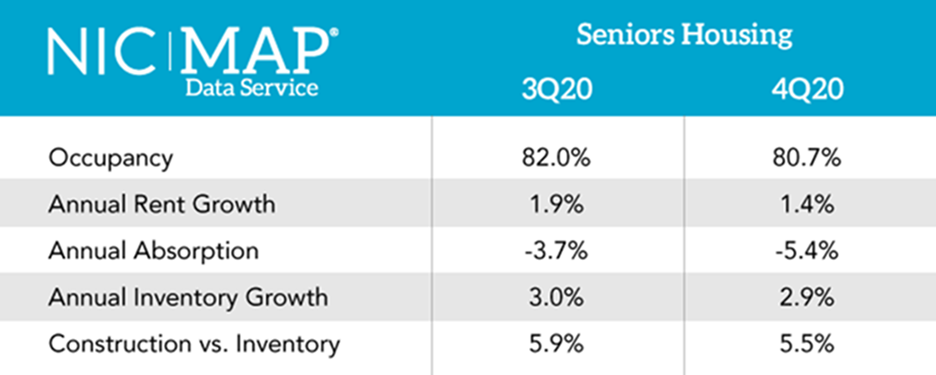

According to the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care (NIC), sharply declining occupancy coupled with the high cost of personal protective equipment, COVID-19 testing and hazard pay for workers is placing the skilled nursing sector under unsustainable financial strain.

Occupancy at U.S. skilled nursing facilities was up marginally between the second and third quarter of 2020 to 74 percent, but remained significantly below levels reported in February (84.9 percent) and March (83.5 percent) when COVID-19 began impacting the U.S., reports NIC.

The road to recovery for assisted living occupancy is going to be a comparatively longer process, Robinson believes. By and large, operators haven’t been able to market their properties during the pandemic, and in some cases referrals from skilled nursing facilities have dried up. What’s more, many families don’t want to place their loved one in a setting where the residents are highly susceptible to the virus.

“We don’t anticipate the assisted living census, which has seen this slow decline, to jump as quickly as what we’ve seen in some of the SNF cases,” said Robinson.

Assisted living occupancy in the U.S. fell 1.3 percentage points to 77.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2020, according to NIC. Since March, assisted living occupancy has fallen by 7.4 percentage points.

Sherman of Live Oak Bank said that some of the borrower issues that lenders are grappling with today were likely evolving before COVID-19 struck. “We’re coming up on nine and 10 months of disruption. We’ve seen deteriorating margins certainly on deals that were profitable. But it’s really the situations that were maybe not profitable prior to COVID — things like lease-up situations, things like value-add strategies — that have been stalled.”

For owners and operators in those stalled situations, there is a cash burn that continues, said Sherman. “Well-capitalized borrowers are absorbing it pretty well — not with a smile on their face, but they are able to do it.”